The Centre Pompidou in Paris chronicles the history of comics. A tribute and journey into the past and future of graphic novels.

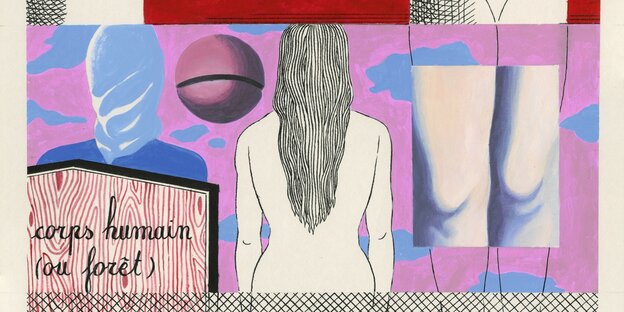

Investigating René Magritte’s Mysterious Motifs: Eric Lambet, “La Saison des Vendanges” Comics: David B. and Éric Lambé

In French it’s called comic. It must be desine. “La BD á tous les étages” – “Comics on all the floors” is the name of an exceptional show at the Centre Pompidou in Paris, combining four exhibitions spread over several floors of the art temple. Translated, “Comics at the Museum” (fifth floor), “Comics. 1964–2024” (sixth floor) and “Corto Maltese. Life as a novel” (second floor). On the ground floor, there is also an immersive holiday camp called “Tenir tête” (roughly “To respond”), designed by the cartoonist Marion Fayolle. Become an illustrator of poetic worlds.

The pavilion exhibition “Corto Maltese”, located in the center of the library, pays homage to the adventurer and anti-hero of the same name by Hugo Pratt through a fascinating array of rare original drawings and watercolors in pastel tones, revealing important motifs and literary elements, a role model for Italian illustrators.

Since 1977, the Centre Pompidou has celebrated the comics art form on several occasions, with exhibitions on important pioneers such as Hergé (2004) and humorist Claire Bretécher (2015). With its two central “floor” exhibitions, it now seeks to present the medium in a comprehensive and contemporary way.

“Manga Magazines. 1964-2024” traces the birth of modern manga in the world of Europe, America and Japan. 1964 is defined as a significant year. While manga had previously been produced primarily for children and young people, new magazines that criticized society and told complex stories were launched in the early 1960s.

exhibition: “La BD à tous les étages” at the Centre Pompidou in Paris runs until November 4. “La bande dessinée au museum”; “Bande dessinée 1964-2024”; “Corto Maltese. A vie Romanesque”; “Tenir tête: Exhibition Atelier de Marion Fayolle”. Admission together: 18 euros

publication: “BD at the Museum”: 25 euros; “Corto Maltese”: 25 euros; “Bande Desiné 1964-2024”: 45 euros

The grand hall where the exhibition opens has ‘counterculture’ as its motto. In the US, cartoonists like Robert Crumb defied the censorship of the ‘comic book code’ of the 1950s by publishing their own cheeky underground magazines, while in France, they published subversive and satirical magazines. Harakiri (precursor Charlie Hebdo) It has been around since the 1960s, when cartoonists like Jean-Marc Reiser and Georges Wolinski developed a caustic and sarcastic humor.

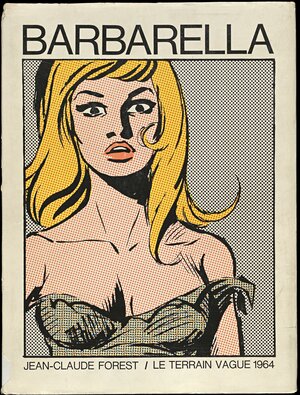

In 1964, Jean-Claude Forest drew the influential science fiction comic “Barbarella” in a Pop Art style, focusing for the first time on confident and erotic female figures. And it also appeared in Japan. width It was also an avant-garde comics magazine in 1964 that allowed a new generation of artists to tell personal and dark stories.

Take a look at Japan

These parallel developments laid the foundation for the sophisticated comics that we see today. Japan has an equal place in the history of comics in the West, and its mangaka (cartoonists) of the 1960s are considered pioneers in telling autobiographical and sophisticated stories in the spirit of today’s graphic novels, even before Europe and America.

The exhibition consists of 12 cabinets arranged thematically. Many popular comic series provide “laughter” (that’s the motto), from Franquin’s chaotic office boy “Gaston” to “Asterix”, Gotlib’s lively antics and Claire Bretécher’s portrait of the 68 generation in “Frustrated”.

Just across the street, the exhibition organizers are dedicating a cabinet to “horror,” where Shigeru Mizuki’s young demon “Kitaro” experiences terrifying adventures in the 1960s, while contemporary American illustrators like Daniel Clowes and Charles Burns dream up nightmarish and bizarre stories for young people in the 1980s and 1990s.

The unconscious is reflected in the “Dream” cabinet, where illustrator Killoffer visualizes his brilliantly surreal black-and-white nightmares. A highlight is the stylish model city designed in 3D by Canadian illustrator Seth for his graphic novel “Clyde Fans” and installed in the “Cities” cabinet.

This show alone is worth a trip to Paris. It brings together many rare original comic pages, along with cover illustrations and animated films by 130 artists, and cleverly juxtaposes old masters like Alberto Breccia with today’s lesser-known works (e.g. Rébecca Dautremer).

The second central presentation, “Comics in the Museum,” is no less provocative. It links essential modernist works from the collection of the Museum of Modern Art at the Centre Pompidou to comic art. The museum rearranges selected works from its diverse collection, from Francis Picabia to Robert and Sonia Delaunay, while the passages between them display classics from the history of comics created at the same time.

With 1905 as the core

Once again, 1905 is the starting point for the development of visual art, such as comics. The artist group “Fauves”, led by Henri Matisse, made their first appearance at the Paris Autumn Salon, causing a great stir because of their new approach to art and their scandalous, bright colors.

In the same year, the first colorful pages of Winsor McCay’s “Little Nemo,” about a boy who experiences fantastic adventures in his dreams, appeared in American newspapers. In almost every episode, McCay experiments with form, playing with the deformation and distortion of the body or the possibilities of page layout.

Also in 1905, Pablo Picasso discovered in Paris American newspaper comics (including George Herriman’s experimental series “Krazy Kat”), which Gertrude Stein had brought from the United States. Other important artists, such as Hergé (shown here with sketches and original pages for Tintin’s moon voyage adventures), Calvo (illustrator of the Resistance animal comic “The Beast is Dead” in which Hitler is caricatured as a wolf, 1942) or Will Eisner, are not to be missed.

The focus is also on 15 contemporary cartoonists who have taken inspiration from or formally alluded to works of modern art in their comics. Belgian artist Éric Lambé took motifs from the work of René Magritte for his enigmatic comics homage, “The Season of the Vintage” (2016). A man in a suit with a bowler hat, a pipe, a Fantômas mask, a woman’s torso…

Next to it hangs Magritte’s painting “Souvenirs of a Journey” from 1926. In the 80s, Italian comics innovator Lorenzo Mattotti points out the nightmarish, deformed creatures and deep, dark backgrounds in Edgar’s illustrations for the poem. Allan Poe (book version Lou Reed’s stage project “The Raven”, 2009) shows aesthetic similarities with Francis Bacon’s self-portrait from 1971.

Pop Art: Barbarella Comics: The Succession of Jean Claude Forest

Frenchman David B. explores the dream world of the poet and theorist in his surrealist comic book “Nick Carter and André Breton” (2019). The centerpiece is an entire wall of his apartment studio, which he describes as a cabinet of curiosities.

Art on every floor

It has become clear that comics are an independent art form, and they thrive not only on graphics but also on narrative elements that museums can only show excerpts of.

A multi-disciplinary marathon exhibition, “Comic on All Floors” sets new standards by juxtaposing Marion Fayolle’s playful comic designs with innovative, analytical dialogues and the “ninth art”, as comics are also called in France.

If possible, it is recommended to visit over several days to see a variety of works and, above all, to enjoy them.